By David Koepsell

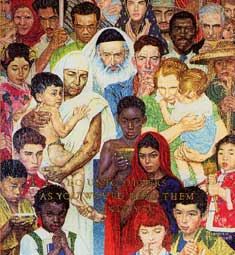

Some secularists may cringe over the potential that the Golden Rule is an immutably divine ethical principle derived from Christian theology. It is this Golden Rule to which the biblical Jesus refers when he admonishes us to love our neighbors as we wish them to love us. In truth, it is and it isn’t; Jesus did not invent it. It dates at least as far back as Confucius, and possibly much further back in philosophies as distinct as Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Judaism. This rule, as with any other rational mode of behavior, admits of certain notable exceptions, so the masochist is not licensed to start flogging people at random, and has an excellent secular defense in the philosophy of Immanuel Kant.

Kant has several formulations of essentially the same rule. The first is: act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it would become a universal law. He justifies this maxim first by arguing that other moral theories, which look to results rather than acts and intentions, cannot be universalized. When a moral precept is based upon results, or is consequentialist, then one cannot make intelligible moral commands. They then come in the form of “you should do X if Y results” or “you should not do Y if Z results.” He argued that the moral property of an act is tied up not with the expectation of a particular outcome, but rather with the action of a “good will,” and thus consequences are irrelevant. He backs this up by appealing to two types of duties: perfect and imperfect. Perfect duties are those which logic demands, such as the maxim not to steal. If we don’t abide by the rule not to steal, then we logically cannot justify property. Lying is another example: without a rule against lying, then language itself—which rests upon implicit agreements to mean what we are saying and that words even have meaning—becomes meaningless.

Imperfect duties come from rules that must exist because they succumb to the universalizability principle. To be consistent, our wills demand that certain behaviors occur in ourselves just as we wish them to occur in others. Kant claims that we can see, by empirical observation, that just as everyone would expect others to aid her or him when she or he is in need, thus she or he must aid others when they are in need, i.e., the Golden Rule.

Now, Kant alleges that he gets to these moral principles by reason alone, and he makes a convincing argument. But there are some noteworthy issues if we take him too seriously, and he doesn’t really give us satisfactory solution. It has been left to other philosophers to try. One prime example is the problem of conflicting duties, such as where the duty not to lie requires us to aid a murderous pursuer looking for his prey, should we happen to know where his potential victim is hiding. Some philosophers have suggested that perhaps certain duties outweigh others (the duty not to abet a murder, for instance, outweighs the duty not to lie) but numerous difficult cases can be imagined, making such weightings Byzantine.

Nonetheless, recent studies indicate that the Golden Rule is naturalistically based. Studies of ape culture, and other animals, have shown that reciprocal altruism abounds in the natural world. This makes a certain amount of sense. If one’s species is to survive, one has to help one’s fellow monkey, armadillo, human, etc. This general rule, simply stated, makes good sense, although there are also certain common-sense exceptions. Also, teaching it may not only make good sense but is already, to a degree, generally acceptable to most children once they develop the psychological capacity for empathy and can envision themselves in the shoes of another. “Now how would you feel, Sally/Billy, if X did Y to you?”

Compassion and empathy seem to be the bases for “ethical” behavior in a number of species, and it seems to be a naturalistically based, utterly rational reaction of a member of a species toward other members of that species. It is consistent with Dawkins’ notion of the selfish gene, which seeks to maximize its survival. It stands opposed to situational ethics or moral relativism, and is a sound basis for moral realism without theology.

David Koepsell is the executive director of the Council for Secular Humanism.

© 2006 Council for Secular Humanism

No comments:

Post a Comment